“How do you sustain hope?” That was the question I was asked recently as a panelist at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights.

It is a fair question. Immigration policies continue to tear families apart. Authoritarian impulses spread easily. Many people long to act for justice but instead feel the weight of exhaustion, fear, or resignation. I have deep empathy for that weariness. Sustaining hope is hard. Retreating into despondency can feel like self-protection.

But despondency is not a neutral option.

At Casa Alterna, hope is not an idea or a mood; it is a practice. It takes shape in solidarity with those society demonizes, in accompanying people whose lives are constrained by systems of cruelty, and in small, steady acts that refuse to let fear have the final word. Hope quietly insists that we act as if a world of belonging and justice is still possible.

Hope is communal.

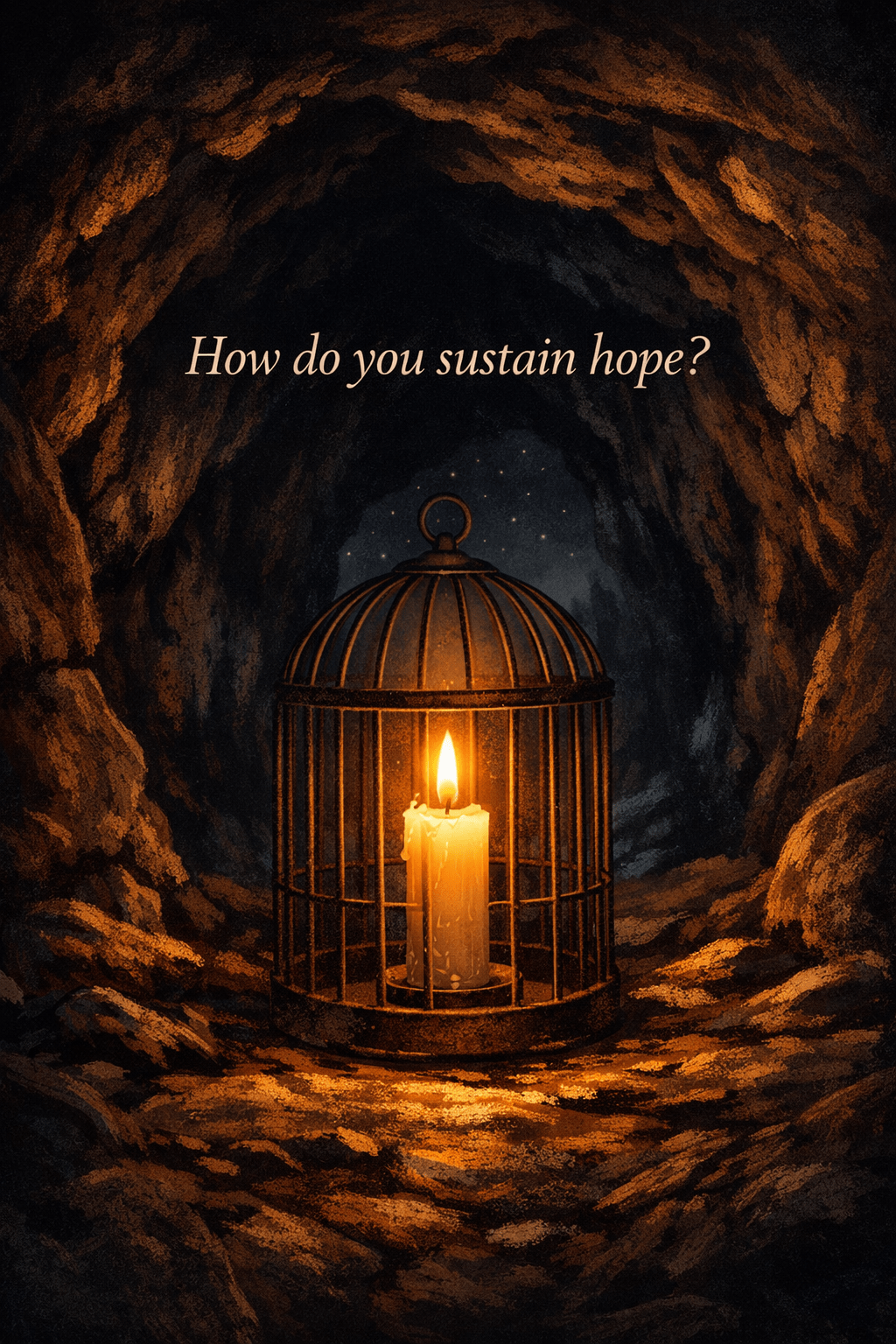

Rooted in shared struggle, hope blooms in unexpected places: food distribution at an apartment complex home to vulnerable immigrant families; radical hospitality offered in places of worship to those navigating what are accurately called “deportation courts,” where justice is not blind but absent; and the quiet courage of volunteers accompanying people standing in the cold and rain outside an ICE field office, caught in the displacement-to-deportation pipeline. Hope also takes shape in simple acts of care that bind us together—like lighting an Advent candle in the dark, not because the darkness has lifted, but because we refuse to surrender to it.

Community is where hope becomes embodied.

Hope emerges wherever people know one another honestly, love one another without condition, serve one another mutually, and celebrate one another with joy. True solidarity requires courage. These days at Casa Alterna, that courage looks like standing alongside people reporting to ICE in sub-freezing temperatures—fingers numb, breath visible—while government scrutiny intensifies. Accompaniment is the task; mutual transformation is the goal. Love crosses borders, liberating both the oppressed and those of us whose privilege might otherwise insulate us from suffering.

Hope has a cost.

In the past year alone, sustaining hope has meant operating with a budget reduced to one-third of what it once was after we chose to walk away from a federal grant. Integrity would not allow us to provide the government with the names and identifying data of the immigrants we serve. It has also meant pioneering a public ministry of hospitality at the gates of ICE and living with the awareness that increased scrutiny has already turned into accusation—and could one day lead to more serious allegations.

I sometimes say that members of our Compas at the Gates of ICE team are canaries in a cave called democracy—not to dramatize our work, but to name a simple reality: when mercy confronts authoritarianism, it carries risk.

Stories carry the weight of hope.

Recently, a former resident—a young mother and her toddler—returned to Casa Alterna to share our communal Christmas meal and meet with her attorney. She first arrived two and a half years ago, alone, unhoused, and pregnant with a child conceived through violence. She entered our meetinghouse as a stranger and became family. She and her baby lived with us for nearly two years, growing toward stability amid ongoing uncertainty. We cannot promise what lies ahead for her, but I hope she knows this: she is held—steadfastly—in love, and she does not face what comes next alone.

Challenges test hope.

Systemic injustice and the fragmentation of community are real and relentless. Beloved Community cannot be sustained through virtual proximity alone; it is forged through deliberate, embodied practices—being with the hungry, the imprisoned, the stranger, and the sick. Distance can feel like wisdom or self-protection, but it is still a choice—one that quietly decides who will bear the cost of injustice and who will only witness it from afar.

Hope is practice.

Hope is not naïve optimism; it is fidelity—showing up again and again, even when success is not guaranteed. When we fail to show up, we are not abandoned or unloved; we simply miss the chance to be human agents of healing in the world. History is shaped by those who intercede.

Hope, then, is walking away from privilege and experimenting with a love that is stronger than fear.

by Anton Flores-Maisonet

At the Threshold

Where in your life might you step closer to suffering, bearing presence rather than keeping distance, and allow hope to take root through your own acts of courage and care?